The Rise of Buffalo's Railways

A lot of cities have nicknames, and Buffalo is no different! It earned the name “Queen City of the Lakes” because, back in the day, the city’s location at the eastern end of the Great Lakes and western end of the Erie Canal made it the nation's largest center for trans-shipment, or moving goods from ship to train and vice versa. At the time, it was second only to Chicago for transporting livestock and was a huge center for handling coal. Buffalo was also the largest grain center in the world.

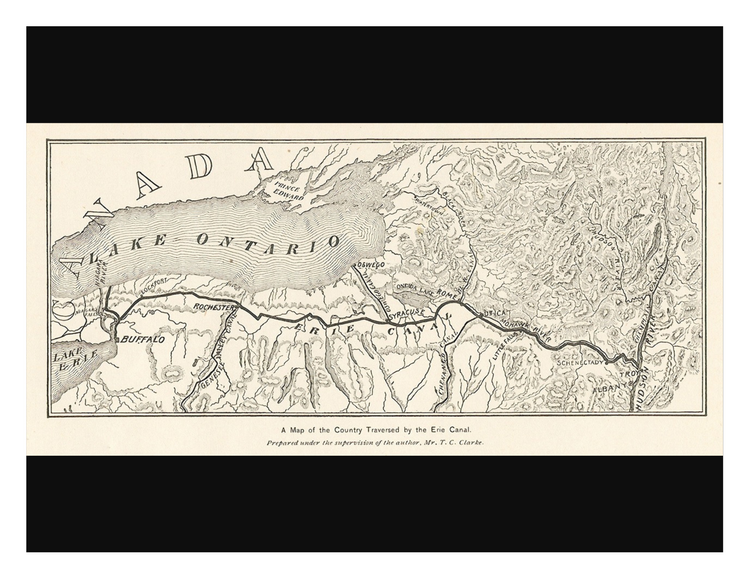

Because the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes used to be the fastest way to move goods in and out of Buffalo, most of Buffalo’s industries were located by the water. The city hit the world stage in 1825 with the completion of the 363-mile Erie Canal, linking Albany to Buffalo and making our city a vital inland port. Grain from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota poured in—milled into flour here or shipped raw to East Coast markets. In 1842, Buffalo’s first grain elevator rose near Buffalo Creek, cementing the city’s role as a major grain hub. Wooden elevators gave way to massive concrete silos, giving Buffalo the world’s largest grain storage capacity by the 20th century. Many are still in use today by companies like General Mills. There’s a reason our city smells like Cheerios!

But how to move the grain other than by water ways? Buffalo’s first steam-powered railroad was built in 1836, linking the Queen City to Niagara Falls. In 1843, the Buffalo and Attica Railroad joined our city to Syracuse, Utica, Schenectady, and Albany. Like the Erie Canal, railroads would play a crucial role in developing Buffalo’s industrial capacity.

By the mid-1800s, Buffalo’s manufacturing scene was hugely diverse and booming. As the city’s economy became increasingly linked with railroads, factories sprang up along the tracks. With the companies and homes largely concentrated along the canals and the waterfront, Buffalo at the time was centered in parts of what are now downtown, the West Side and South Buffalo. Most of the city as we know it today was vacant and undeveloped.

New York Central Railroad wanted to encourage new industrial growth in some of the vacant lands – now the East Side and North Buffalo. They began laying tracks in a “belt loop” around Buffalo in 1871. The new Belt Line opened in 1883 and caused a boom in industrial development around the city.

Buffalo’s industrial boom turned into more of a Big Bang when Nicola Tesla’s hydroelectric plant in Niagara Falls changed the game. A flip of a switch in 1896 brought a regular supply of electricity to the Queen City. Between the railroads and the new power supply, 412 new factories opened in Buffalo between 1890 and 1900 — 300 from brand-new companies!

Although an 1857 financial panic and the later Civil War had sparked a two-decade pause in national railroad construction, Buffalo continued to prosper. By 1862, it had a population of 100,000 and was served by eight major railroad companies. The first structure of what was to become New York Central Railroad’s final downtown Exchange Street station was erected in 1870 between Michigan and Washington Streets. In 1881, four people were killed when the roof of the Exchange Street station collapsed. The tragedy spurred new calls for a new, larger train station.

The growth of the railways and the affordable hydroelectric power meant that companies could move outward. As businesses spread eastward, residential neighborhoods and stores followed. The Belt Line played a key role, spreading out the city’s industrial development, strengthening ties between factories and railroads, and connecting Buffalo’s commuters and freight to America’s railway system. New York Central’s main station at Exchange Street, where trains from all over America arrived and departed every day, served as the Belt Line’s center. It also provided commuter rail service from any area in the city to any other part for a nickel fare, opening whole new areas for residential and industrial development. The Buffalo Central Terminal’s Belt Line station is still standing along the tracks, east of the Terminal, and those tracks are still used by CSX to transport freight.

As the city’s industrial and residential areas grew, so did its rail network. In the late 1800s, sparked by the Belt Line’s success, some “spasmodic movements concerning better station and terminal facilities started moving ahead” with the idea of a union terminal. For clarity’s sake, a union terminal is a station formed when two or more railroads merge their needs and agree to share costs by bringing their trains into the same depot.

Map courtesy of ErieCanal.org.

-

An Introduction to the Tour

-

Meet the Narrator: Drew Canfield

-

Welcome to Buffalo Central Terminal

-

Meet the Narrator: Dr. Ursuline Bankhead

-

The Rise of Buffalo's Railways

-

Meet the Narrator: Thea Hassan

-

Location, Location, Location

-

Meet the Narrator: Terry Alford

-

Moved by Community: East Side Evolution

-

The Big Build: 1926-1929

-

An Art Deco Icon

-

BONUS: The Grandest of Openings

-

BONUS: The Way Things Were

-

Meet the Narrator: Robby Takac

-

A Welcoming Sight: The Entry Plaza

-

Meet the Narrator: I'Jaz J'aciel

-

BONUS: Mafia Ties

-

What’s In a Name? The Connecting Streets

-

The Jewel: The Main Terminal Building

-

A Vision of Beauty: The Passenger Concourse

-

Waiting Never Felt So Good

-

A Passenger’s Point of View

-

Mail, Packages, and Baggage Galore

-

Neither Snow nor Rain nor Heat nor Gloom of Night…

-

The First Building: Railway Express Agency Terminal Building

-

Easy Access: The Train Concourse and Platforms

-

Open For Business: The First 25 Years (1929-1954)

-

BONUS: A Gateway For Black Americans

-

BONUS: The War Years

-

Harbingers of the Coming Collapse

-

Final Boarding Call: The Last 25 Years (1955-1979)

-

A Light at the End of the Tunnel

-

All Aboard for a New Journey