Library

This space reminds us that the fight against slavery was not just one story—it was a movement. And one of the remarkable things about that movement is that it was one of the first interracial, co-ed efforts in the United States. Men and women, Black and white, free and enslaved, all took part in shaping the abolitionist cause.

But abolitionism was not always unified. Not all abolitionists participated in the Underground Railroad. Some wrote articles, some gave speeches, and others worked within politics. Each person contributed in their own way.

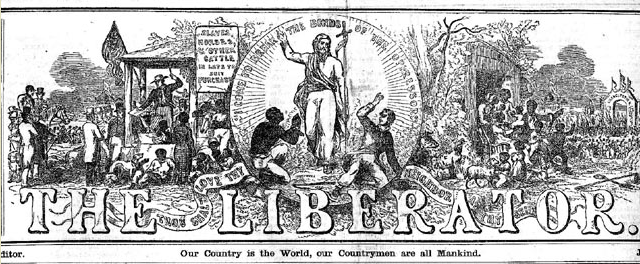

In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison founded the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. His voice marked a shift in the movement—from gradual approaches like colonization to a louder, uncompromising call for the immediate end of slavery. Around the same time, Nat Turner led a rebellion in Virginia. Though unsuccessful, it shook the South and led to harsher slave codes. After escaping enslavement from Maryland in 1838, Frederick Douglass became a lecturer for the abolitionist movement, recounting his experiences and pushing for emancipation and civil rights.

Literature also shaped the debate. In 1852, Ohioan Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that brought the horrors of slavery into the homes of Northern readers. The character of Eliza, who famously crosses the icy Ohio River with her child, is believed to be based on real stories, though her tale isn’t documented. Still, her bravery stands as a symbol of the risks so many took.

The fight wasn’t only on the page. In 1856, Senator Charles Sumner gave a fiery speech condemning slavery. Days later, he was beaten nearly to death on the Senate floor by Congressman Preston Brooks. The violence of that moment showed just how divisive and dangerous the issue had become.

Even within the abolitionist movement, tensions existed. Women like Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton traveled to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London, only to be denied full participation. They were allowed to attend—but were hidden behind a curtain to remain silent.

And while the stories of white abolitionists were celebrated in later decades, Black abolitionists and freedom seekers themselves were often overlooked. In the 1930s, the Underground Railroad was romanticized in ways that focused more on heroic white families than on the enslaved people who risked their lives. Today, historians are working to correct that, ensuring credit is given where's due.

When you’re ready, let’s head upstairs.