Dining Room

Now, let’s step into the dining room.

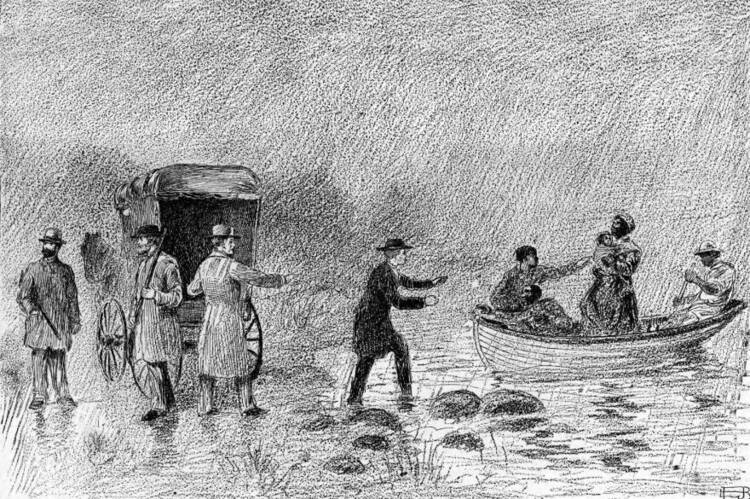

Participation in the Underground Railroad was always risky. Slave laws made it illegal not only to help enslaved people escape, but eventually even to refuse to assist slave catchers.

Thomas Rotch, careful by nature, often sought legal advice. In the 1820s, his lawyer told him he could not be prosecuted so long as he didn’t physically remove someone from a slave state. His wealth and standing in Kendal offered him additional protection. Even if caught, it’s likely he would have faced little more than a fine. But this knowledge did little to ease the anxiety he and his wife Charity must have felt with regards to the safety and well-being of those they were aiding.

For others, the risks were greater. White abolitionists in pro-slavery towns could be jailed. But Black abolitionists faced far worse: kidnapping, enslavement, or death.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 raised the stakes even higher. It required every citizen—North and South—to aid in the capture of runaways. Judges were paid more to return accused individuals to slavery than to release them, leading to countless free African Americans being kidnapped and enslaved. Since Black men and women couldn’t testify in court, they had little way to defend themselves.

This meant that even in so-called “free states,” freedom was never guaranteed.

As you stand here, imagine the conversations that could have taken place around a dining room table—heated debates, urgent planning, and perhaps even the quiet relief of a meal shared in safety.

When you're ready, let's step into the next room.