The Star Spangled Banner Story

Upper Marlboro, Saturday, August 26, 1814

Roused from their exhausted sleep at noon Friday, the British troops marched in oppressive heat toward Upper Marlboro, continuing without halting until they arrived at dusk. On Saturday, the British troop departure seemed like a cause for celebration to Dr. William Beanes, who hosted the commanders on their way to Washington. Robert Bowie, the distinguished former governor of Maryland, was one of the guests invited to join Beanes Saturday afternoon, along with the doctor’s brother, and three other acquaintances. More than a hundred stragglers were roaming the countryside, pillaging homes, taking horses, and stealing foods. As Beanes and Governor Bowie strolled around the doctor’s property, they encountered a British soldier trying to “steal the refreshments” from the garden and forced him to surrender. The guests soon realized that more British were on the loose. Bowie, who had commanded a militia company during the revolution, proposed capturing them. Set out armed with a fowling piece caught at least three stragglers. The town was soon in an uproar over fears of a British retaliation. Bowie, concerned that upset residents would release the prisoners, turned to two reliable local brothers, John and Benjamin Hodges of Darnall’s Chance, to move them to a safer location. The prisoners were taken nine miles northeast to the town of Queen Anne, on the upper Patuxent River, where residents mounted a guard.

That night, one or more escaped British stragglers made their way from Upper Marlboro and were picked up by British patrols. Taken to Ross at the British camp at Nottingham, they reported that their erstwhile host, Dr. Beanes, had captured some of the men. Ross was infuriated; Beanes had been “one of those who had met us with a flag on our entrance into Marlboro,” the general observed. For Ross it was a question of honor. He had gone to extremes to respect private property and treat civilians with courtesy, particularly those he considered gentlemen. At 1am Sunday, the British horsemen thundered into Upper Marlboro and rode to Academy Hill Beanes was “taken from his bed in the midst of his family, and hurried off almost without clothes,” according to an American complaint delivered to the British. The doctor was handled so roughly and hurriedly that his spectacles were left behind. Two of his guests were taken as well, and the three men were tossed onto horses without saddles. The officer of the British horsemen left town with a warning: “Unless they were returned before 12 o’clock the next day, they would lay the town in ashes,” a witness reported.

Upper Marlboro was in a panic after the horsemen rode off. John Hodges was awoken by neighbors, who told him of the British threat and asked that he bring the prisoners back from Queen Anne. Bowie at first refused to approve their release, but relented after hearing more details of the British threat. The prisoners were returned and Upper Marlboro was spared.

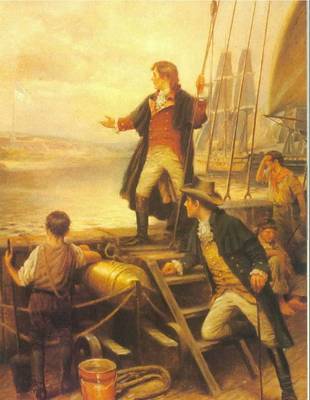

On the Wednesday before the fleet departed from Benedict, an American emissary, Richard West, arrived to plead for the release of Dr. Beanes and the other two American prisoners. West, a close friend of Beanes, lived near Upper Marlboro at the Woodyard plantation with his wife, an older sister of Francis Scott Key’s wife. Ross released the other two Americans, but not Beanes. West would petition Madison to have Key seek Beanes release. Madison agreed and sent American agent for prisoners of war officer John Skinner. Despite Skinner’s reservations, he and Key were well matched for the mission. Key brought “tact and persuasive manners” to the mission, Skinner later noted. For his part, Skinner knew how to deal with the British. On board the British truce ship, Key and Skinner negotiated the release of Beanes successfully, but were asked to remain on board until the Battle for Baltimore had concluded. Key and Skinner paced the deck in painful suspense, anxiously awaiting the return of day, looking every few minutes at their watches. Finally, the first pale signs of dawn brightened the sky. Even before there was enough light to see distant objects, they trained their glasses on the fort, as Key later said “uncertain whether they should see there the stars and stripes, of the flag of the enemy” Through the morning mist, the Americans finally could make out a flag, towering over the grassy knoll of the ramparts. But the banner hung limply from the flagpole, and it was impossible to tell if it was American or British. As the morning lightened, a slight breeze blew fitfully from the northeast, scattering the mist . The flag stirred with a tantalizing hint, but Key and Skinner remained unsure. Finally, a beam of sunlight illuminated the flag, revealing it to be American. Key was overcome with relief. By late Friday afternoon, the British had finished loading their ships and Key, Skinner, Beanes, and the American crew were told they were free. As the truce ship sailed toward Baltimore that evening, Key worked on his composition, a song, the “Star Spangled Banner.”

Excerpted from “Through the Perilous Fight,” by Steve Vogel, published in 2013 by Random House.

-

Bladensburg in 1814

-

Unorganized and Unprepared

-

Surge Across the Bridge

-

Second American Line

-

Marching Across Prince George's County

-

British March & Colonial Marines

-

Famous Footsteps

-

Bunker Hill Road Retreat

-

Joshua Barney at the Third Line

-

American Stand at the Third Line

-

Flanked and Retreat

-

Barney Wounded

-

Washington Burned

-

The Star Spangled Banner Story

-

The Bladensburg Dueling Grounds