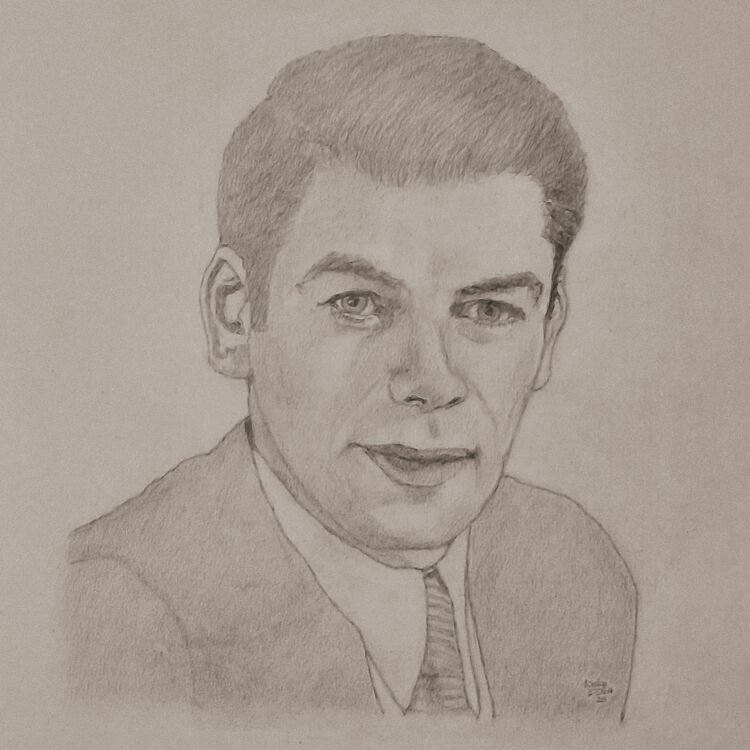

Paul Muni

Paul Muni was born Frederich Meshilem Meier Weisenfreund in 1895, to parents who were Yiddish actors. He too became a Yiddish actor, and he played on the Yiddish stage at least from 1916 to 1932.

Muni acted in New York City's National Theatre in a Yiddish play that opened on March 24, 1932, while at the same time starring in the English-language film, "Scarface," in which he played the title role.

And this film was released two weeks after the following article was published in the Forward, on April 9 of that year.

In a 1932 article written for the Jewish Forward newspaper, Muni decries the state of the Yiddish theatre at that time, and he expresses a desire for a better, Yiddish theatre.

Here is a partial version of his article:

"I have always struggled with the idea of whether I should accept the invitation of the editor of the "Forward" to participate in the discussion about the Yiddish theatre, because I understand that there are no health benefits to the participants. If one is only serious and honest in expressing an opinion, one must face this or that person's scorn, and here and there you tread on some toes, which hurts, and of course people will get angry. But that did not stop me from writing. It is not easy for someone who is "full," to speak about the condition of the hungry. What he does not say will immediately be replaced by the teasing of a "self-satisfied" person, from one who is concerned with a livelihood. And their words shall be heard before they are heard.

Not intended to be included in the discussion, it could also be easily "explained" by "smart people" in their own way.

“Aha, you see,” the “wise men” point out, “We already said to you – what does he care about Yiddish theatre? He is with "them," it is good for him, and the Yiddish stage for him is in left field. I do not. He doesn't even want to look at her side, and his former colleagues don't care about him."

At such a value, I imagine, people would speak more clearly and meaningfully.

Both sides, naturally, are incorrect. I have spent quite a few years in the Yiddish theatre. I started to take my first steps to begin my theatre career on the Yiddish stage. Therefore I need to say, isn’t the Yiddish theatre then dear to me? That I would do everything that is possible for me to help it?

My sympathies are with my colleagues on the Yiddish stage. For them now it is bitter, difficult, and I very well understand their situation.

I have already been away from the Yiddish stage for six to seven years. I've been through a lot, and I think, that now I can see such things more clearer, that I can understand things, and therefore I will exercise my right to express an opinion.

I do not agree with those who say that, because of the blocked immigration, the Yiddish theatre is suffering. They point to the local Germans, French and other nations as evidence. They don’t have any theatres in their languages. But this evidence is no evidence at all. And do the great “workers” with the “National Labor Unions” and “Bris Avrohom’s” have them? And do large daily newspapers with circulations of tens of hundred thousands have them?

Jews are a people who live differently, settling themselves into a country with their sukkahs and synagogues and theatres. The same measure cannot be applied to them as to other peoples, the usual scale. That's how it is.

Even if a Jew wants to forget their Jewishness, wants to get mixed up with the lives around him, they tell him don’t. They explain to him who he is, and when it is necessary, they arouse his Jewishness with a bang. Willingly or unwillingly, he gets his Yiddish mixed up, he begins to look with warm glances at his own, at what his parents have left as an inheritance.

And this Yiddish theatre has left an inheritance of a generation of beautiful artists, from a generation of proud actors. He suffers, however, from a serious illness. He suffers from the fact that he did not change with the immigrant who brought him here.

They still play in all the Yiddish theatres for an audience that is backward. However quickly the audience can free itself, this is how quickly they will attract new, modern Yiddish audience, and everything will be better for the future of Yiddish theatre.

The Yiddish theatre was founded for immigrants. The former immigrant, however, has already “outgrown” it, and they have become a new person, with a new taste, a new way of looking at things. His heart is in the big city. The Yiddish theatre has not yet shown that it can adapt to the former immigrant or to his child.

The child has grown up, his old clothes are torn; they are now tight, narrow, and not adapted to his grown limbs. In this lies the tragedy of Yiddish theatre.

I mean that the Yiddish audience, indeed the taller adult would like to go to the Yiddish theatre, if the theatre could be comparable in its quality to other theatres. If the Jewish-American young man and woman could be proud of Yiddish theatre as something that “his people” has created, he will visit it and support it with love.

I know this from experience. I know many Jewish-American youth who don’t know a word of Yiddish and are nevertheless frequent attendees to Schwartz’s Art Theatre. Yet now they speak with love, and they talk separately about what they had seen there. So that the youth may come to the Yiddish theatre, the theatre needs to be in quality no worse than the American one. On the contrary, even better.

And this should not be an incredible achievement. Because the Yiddish stage has acting material. One can count a large number of Yiddish actors who, under the friendly hand of stage directors, would enhance the Yiddish stage.

But … everything is now so neglected, orphaned, forsaken. The Yiddish theatre world is immersed in a quagmire of helplessness and disappointed hopes. It lacks youth. It lacks youth in the theatre, and youth on the stage. And how shall it have youth?

When I was a young boy, a beginner, I thought, I looked on with trepidation and dismay on several ensembles of actors, such as Lipzin, Kalish, Tornberg, Blank, Moshkovich. They ignited my blood and my fantasy. To play with them was my wildest dream. I looked up to them, and they fueled my ambition.

To whom can young actor of today look up to? What great artist can now stimulate and fuel him? What kind of ideals are moving the stage of Yiddish theatre forward now?

I don't think that the Yiddish theatre has any great artists. It’s just that their methods are old, their view of the theatre, and their approach to their acting is old.

The tone of the Yiddish stage is outdated. Fifteen to twenty years ago the tone was probably fresh and new. Now, however, it is wrong, worn out. And young, capable actors must adapt to it. They have lost their sense for the stage, their ambition; they are old and forlorn in their youth. When I go to the Yiddish theatre and see the young elders, my soul becomes sour, and my heart bitter. They must be the fresh stream that will water the soil of this Yiddish theatre ...

This is what is becoming of the actor at the Yiddish theatre. Their teachers are the actors of the old fashion, they, who fifteen to twenty years ago led the grandeur.

Because of them, there aren’t any writers who come to the Yiddish stage, because no true writer will provide the gossip that they need.

Because of them they cannot find any stage directors, because who cannot stage a play?

They themselves are the regisseurs, themselves the writer, themselves the entire cook.

If only the senior actors could be blamed for this difficult situation, it would be fine and good. They could be removed, let's say, and everything would be fine. However, looking at the entire situation, there are many, many other factors that cause damage. Each factor in and of itself is not at all to blame; on the contrary, perhaps it is useful for the Yiddish theatre. Together, they are entangled, one with the other, and they create a dark wall that surrounds the Yiddish theatre, not allowing in any light and suffocating the entire theatre.

Every union is good, necessary, a useful thing. The “Union Rules and Regulations”, however, becomes a heavy burden that suffocates and oppresses the Yiddish theatre. Mostly the actors gets squeezed under the laws and the “rulings” of the unions.

It got to such a point that some actors who wanted to maintain a place in a theatre must socialize and mingle in union politics. Instead of busying themselves with their art and letting Guskin run the union, they seek to become influential members on the Executive Board, because this helps them acquire better roles in the theatre. The manager, knowing this, that they are not fathers in the union, has respect for them.

If there were directors at the Yiddish theatre, this would certainly not have happened. Instead of engaging in union politics, actors would engage in roles.

These are all little things, corners of tangled and twisted cluster, which is called “Yiddish Theatre." Perhaps these are bitter words. However, I believe that everyone, both the actors, as well as the unions and managers – everyone must change, to adapt to the new times, to the new circumstances.

The Yiddish theatre now throws itself into convulsions. These are the convulsions of a living body that must change, expand and can’t because of the “straight jacket” in which it was fitted, and from this “straight jacket” they must be taken out of it as soon as possible.

I am convinced that the Yiddish theatre can exist, must exist, if one would only carry out the absolutely necessary reforms. You will ask me: how do you carry them out?

To this there can be only one answer: From beginning to end, from top to bottom, no medicine can help here. An operation is required here. If this requires a revolution, a revolution in the minds, and in the methods of everyone who is connected to the Yiddish theatre. Whether they have the strength and the courage for such a change remains to be seen.

I know that it hurts a lot. We have a lot of very good talented, able actors. They are lost because they lack the one who used to give them an education, the opportunity. They die away, because there is a lack of sunlight, watering; because thick walls surround the Yiddish theatre and block it, hide it.

When the walls are torn down, the Yiddish theatre will continue to exist and contribute to Jewish life in America."