Leah Erwin & Sandy Erwin

Born between 1800 and 1806, Leah was likely the daughter of Leah (I) and Jo. Leah spent much of her adult life as the cook and housekeeper for the Vances. In 1835, Priscilla Vance willed Leah to her son, David Jr. By this time, Leah and other men, women, and children enslaved by the Vances were transitioning from the Reems Creek Valley plantation to the drover stand in present-day Madison County. Leah continued to cook for the Vances and their customers at the drover stand, earning a reputation as one of the best cooks in the region. Her day began before the sun rose, prepping food for everyone at the stand, and finished after sunset—every day. Working over a large cook fire, Leah lifted heavy iron pots and pans, chopped vegetables from the garden, baked bread, and prepared the winter store of sauerkraut.

In 1844, Leah and her four children were put up for auction as part of David Jr.’s estate sale. David’s widow, Mira Vance, re-purchased several of the enslaved people put up for sale, including Leah and her four children. Leah remained with Mira until emancipation and seems to have maintained a relationship with her former enslaver. In 1878, Leah and her husband, Sandy Erwin, attended Mira’s funeral.

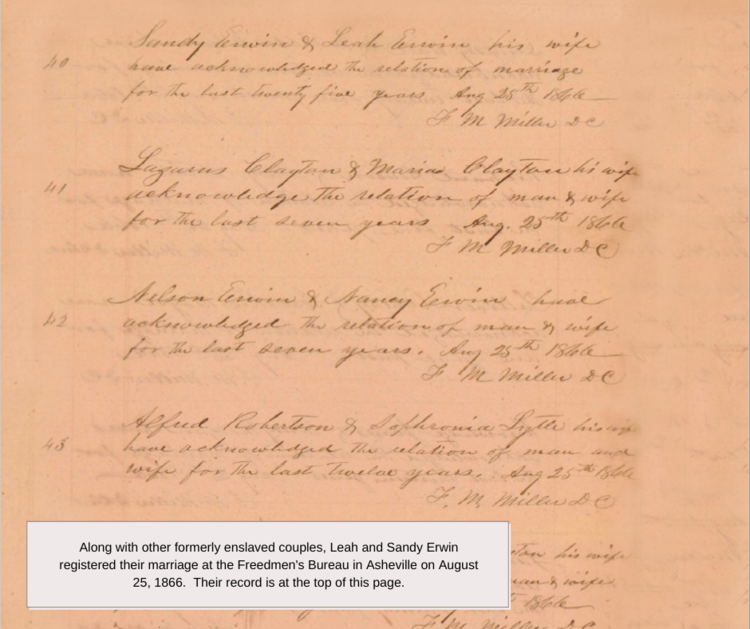

Like other couples, Leah and Sandy Erwin registered their marriage at the Freedmen’s Bureau office in Asheville in 1866. Though marriages between enslaved people were not legally recognized, the couple stated that they had lived as husband and wife since 1841. Their relationship may have been complicated by the fact that Sandy Erwin was not owned outright by the Vances. As his last name attests, Sandy was owned by the Erwins, who were relations of Mira Vance’s mother, Hannah Erwin Baird. It seems likely that Hannah hired out Sandy’s labor to her daughter and son-in-law. In 1849, Hannah willed Sandy to her two sons, requesting that they not sell him out of the family. They may have sold or given Sandy to their sister, Mira, at this time. The 1850 slave schedule for Mira Vance lists a 40-year-old enslaved man who is likely Sandy. The 1860 slave schedule lists a 51-year-old enslaved man.

Sandy and Leah are recorded in both the 1870 and 1880 censuses. Sandy was a farmer who could neither read nor write, although by 1880 he could read. The couple’s property in Sulphur Springs Township was valued at $60 in 1870. By 1880, Leah and Sandy were living in Asheville with their granddaughters, Leah and Jennie Williams.

-

Richard & Aggy

-

Richard Vance II

-

Hudson Vance & Ann

-

Jo and Leah

-

Leah Erwin & Sandy Erwin

-

May

-

Venus

-

Abram Vance

-

Jim

-

Hannah Prestwood

-

Isaac, Peter, & Harry

-

Esther, Isham, & Washington

-

Moses & Philip

-

James Vance, Simon Vance, & Dory

-

Jane & Wilson